Getting your home robot ready according to history

A historical grounding of how industrializing domestic spaces robotic can accelerate the adoption of home robotics

Conversations about domestic robotics tend to all end up in the same place. We simply aren’t there yet. We are so far away from creating a robot that can reliably move through cluttered and inconsistent environments, understand context, improvise and execute tasks reliably, and generally replace human domestic labor in the manner in which we do it today.

We can all agree on this but what usually follows is where I argue we need to alter our perspective.

The absence of a generalist humanoid robot is frequently taken to mean that domestic automation itself must wait or that we can only hope to implement the giant puppetry of teleoperative robotics which are merely a controversial skin for outsourcing human labor. Homes remain unchanged, while expectations are placed on future machines to adapt to environments that were never designed with automation in mind. The burden of adaptation is pushed entirely onto the technology, rather than shared with the spaces in which that technology is meant to operate. I argue that this framing is slowing us down.

Robotic assistance is not out of reach for the home. What is missing is the willingness to reconfigure our spaces to allow existing robotic systems to be adopted properly and function for us efficiently. While it’s true that today’s robots perform poorly in spaces that are visually noisy, spatially ambiguous, and organized around aesthetic or social priorities rather than work, today’s robotic automation is already highly capable in environments that are structured, predictable, and machine-legible. Modern homes can benefit from domestic automation as soon as they reconfigure to optimize themselves for it.

We are wasting valuable potential by waiting for increasingly sophisticated machines when a more immediate intervention is available: rethinking the design of domestic service spaces so that the robotics we already have can be put to use. Kitchens, laundry rooms, pantries, and delivery interfaces are work environments where hours of our labor each day takes place, and they can either enable or obstruct the assistance of automation. Reconfiguring these spaces won’t replace the future of generalist humanoid robots in the home. But it will help us see the benefits of robotic automation now and ease our pathway towards the home of the future.

Homes Have Always Changed to Fit New Tools

The idea that domestic environments should remain fixed while appliances evolve to fit them goes against our historical evolution. Over the past century, homes have repeatedly been reshaped in response to new technologies that altered how domestic labor was performed.

When gas and electricity entered the home, room layouts changed. When refrigerators, washing machines, and electric ranges became common, kitchens and utility spaces were reorganized around them. Built-in cabinetry replaced freestanding furniture. Counter heights were standardized. Storage of ingredients and tools became more systematic. Circulation paths were shortened and optimised. These changes were not stylistic, but practical accommodations made so that new tools could function effectively. Households didn’t wait for appliances to become flexible enough to fit any space, they redesigned spaces to support the appliances in order to extract their benefit.

This process was not informal or accidental. In the early twentieth century, domestic labor became a serious study. Architects, engineers, and home economists treated the home as a site of work, and subjected it to the same scrutiny as factories and offices. Movement was analyzed. Steps were counted. Tasks were broken down. Space was organized to reduce unnecessary effort and time.

The goal of this work was not to industrialize life for its own sake, but to relieve the burden of repetitive labor by designing environments that worked better.

Robotics now presents a similar opportunity. Like early domestic appliances, contemporary robotic systems perform well under certain conditions and poorly under others. The mismatch between their capabilities and the spaces we expect them to operate in is not unprecedented. It is actually quite familiar and has wonderful historical precedent. The question is not whether homes should change to accommodate a new home innovation like robotics. The historical record suggests that they will and always do.

The Pre-Standardized Domestic Interiors of the 1900–1920s

At the start of the twentieth century, domestic interiors and specifically kitchens, were rarely designed as work environments. Instead, they were assembled incrementally, shaped by furniture availability, building and space constraints, and tradition rather than by an understanding of workflow. Storage was usually improvised, work surfaces varied in height and placement, and tools were scattered across the room without a consistent system tying them together.

This mattered because domestic labor was physically demanding not simply due to the nature of the work, but because the space itself imposed inefficiencies. Tasks required excessive walking, bending, and reaching. Tools were not located where they were needed. Ingredients, utensils, and equipment were often stored far from the point of use. In effect, the environment created more work for the user.

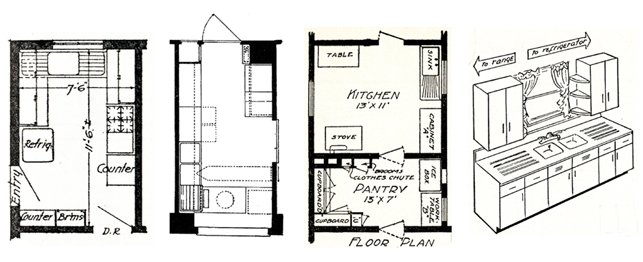

Kitchen plans from this period reflect this lack of intentionality. Circulation paths were indirect. Furniture stood in for built-in infrastructure. There was almost not thought or agreement about where food preparation should occur or how tasks should progress. What we now recognize as the field and art of “kitchen design” barely existed as a concept.

From today's perspective, these early kitchens resemble what robotics researchers would describe as unstructured environments: spaces rich in variation and personalization, but horribly suited to repeatable tasks or the deployment of a standardized robot. The comparison is useful because it highlights an enduring principle. When environments are unstructured, even capable tools struggle to deliver meaningful efficiency gains.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Domestic Labor Design of the 1910s–1950s

The transformation of the kitchen into an optimised workspace wasn’t an accident. It emerged from a broader cultural and intellectual shift that treated efficiency as both a scientific and moral concern.

The Efficiency Movement

During the Progressive Era, American faith in science and expertise exploded. The Efficiency Movement, led by figures like Frederick Winslow Taylor, argued that waste permeated modern life, from factories and government offices to households. Inefficiency was framed not only as an economic problem, but as a social one: wasted time, energy, and resources were seen as avoidable.

These ideas resonated beyond industry. They influenced conservation efforts, public administration, and the reform of domestic spaces. President Theodore Roosevelt openly supported efficiency principles, and this pervasive belief that engineers could improve everyday life persisted well into the mid-twentieth century.

Home Economics and Household Engineering

Home economics became the primary vehicle through which efficiency thinking entered the home. Christine Frederick was one of the practice’s most influential advocates. Beginning in 1912, she published a series of articles on “New Housekeeping,” arguing that domestic labor could be analyzed, measured, and improved using the same principles applied to industrial work.

Frederick treated her own kitchen as an efficiency laboratory. She conducted time-and-motion studies, tracked steps, and reorganized space to reduce unnecessary effort. Her 1919 book Household Engineering: Scientific Management in the Home presented domestic work as legitimate labor. She firmly defined domestic labor as worthy of systematic and scientific study. What mattered most was not the specific layouts she proposed, but the premise underlying them: that space could be designed to alleviate labor and improve efficiency. Efficiency was not about working harder or better; it was about designing environments that made work easier by default.

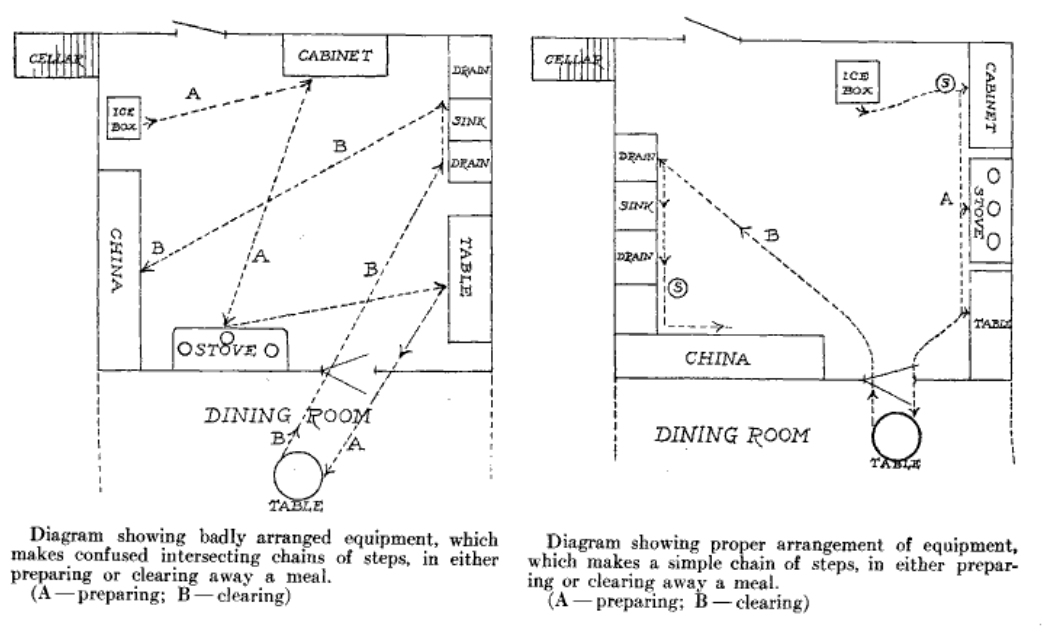

Christine Fredericks, The New Housekeeping 1913

Lillian Gilbreth and the Logic of Motion

Lillian Moller Gilbreth extended these ideas through her work in psychology and industrial engineering. Together with her husband Frank Gilbreth, she developed time-and-motion studies that broke work into smaller components for analysis and optimisation. After Frank’s death, and amid discrimination in industrial engineering, she increasingly applied these methods to domestic settings.

The kitchen work triangle which linked the sink, stove, and refrigerator, was not just a stylistic recommendation. It was a spatial abstraction of labor flow. By minimizing distance between the most frequently used work centers, Gilbreth aimed to reduce fatigue and wasted motion. Her work reframed the kitchen as a system. Tasks were not isolated actions; they were sequences which could be supported or hindered by the space in which they were performed. The environment became an active participant in labor.

Lillian Moller Gilbreth (1878-1972) - The Architectural Review

The State as Domestic Designer

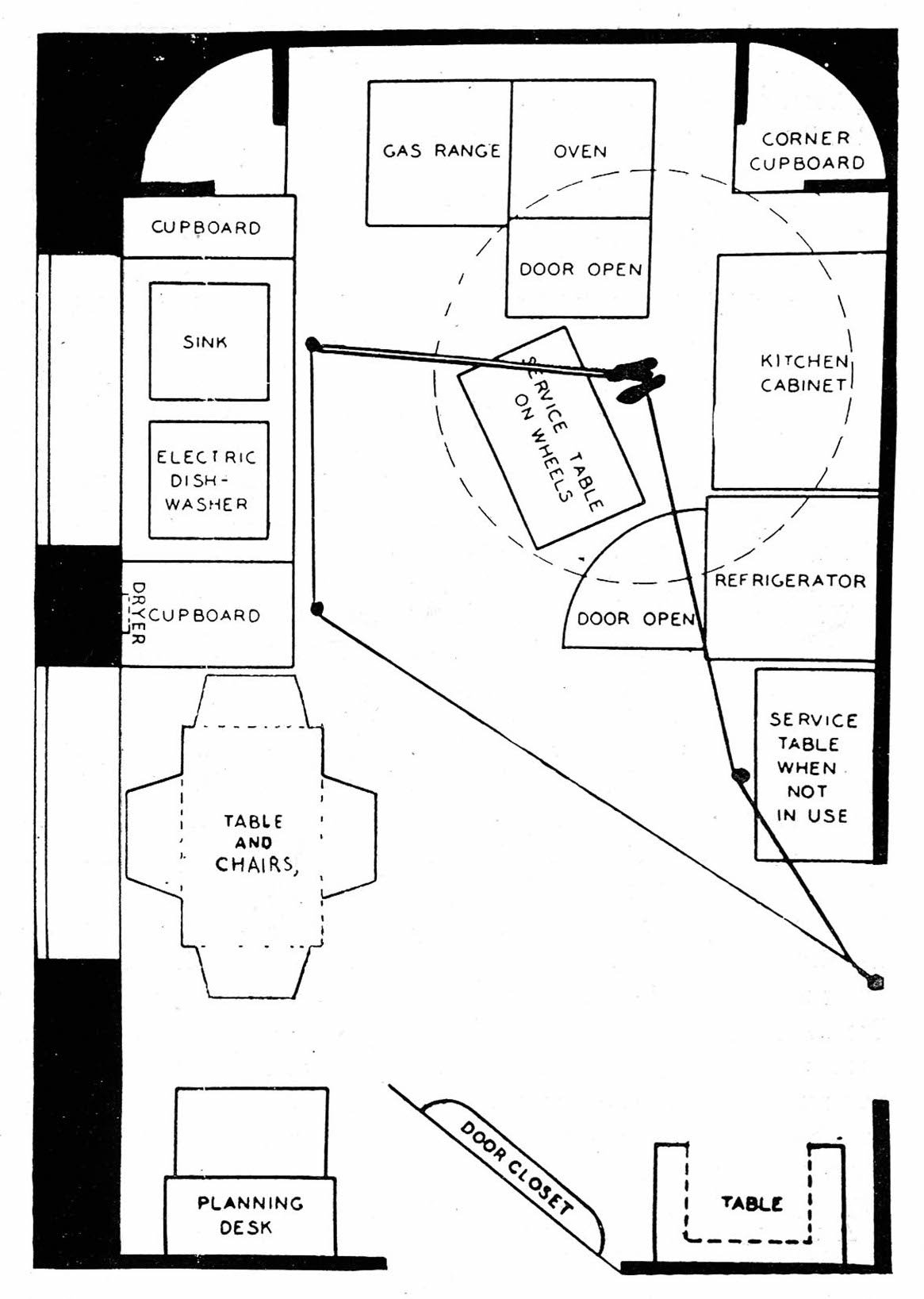

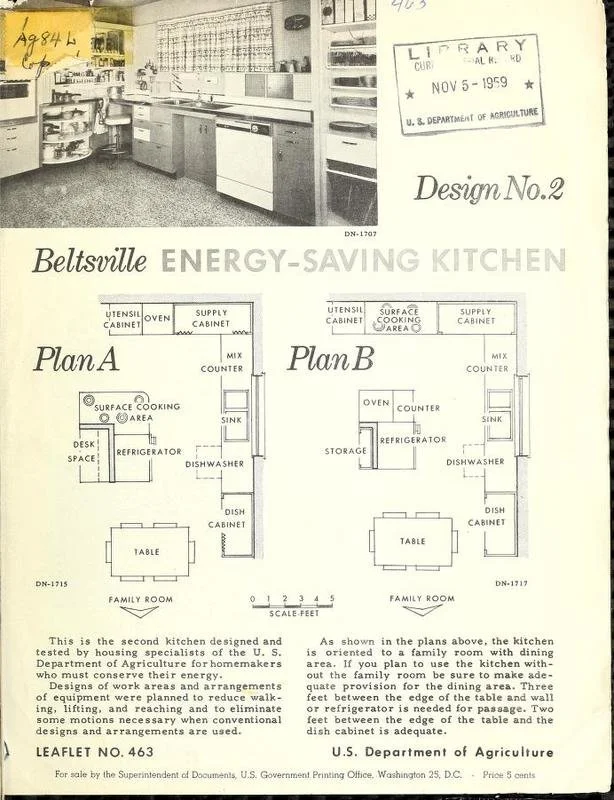

By mid-century, these ideas had become institutionalized. Government agencies, particularly the USDA, produced scientifically tested kitchen designs intended to reduce household labor through layout alone. Publications and films such as A Step-Saving Kitchen translated research into practical guidance for builders and homeowners.

These efforts treated domestic design as infrastructure. The goal was not luxury or display, but reliable, repeatable reduction of effort across millions of homes.

Step-Saving Kitchens - National Agricultural Library - USDA

The Appliance Frenzy: When Homes Were Reconfigured to Fit Machines

The widespread adoption of domestic appliances in the early and mid-twentieth century is the most direct historical parallel to today’s moment in robotics. Refrigerators, washing machines, electric ranges, and dishwashers didn’t simply appear and integrate seamlessly into the existing layouts of homes. They forced an upheaval and reconfiguration of the domestic space.

Early appliances were bulky and completely constrained by utilities across the board. Refrigerators required ventilation and proximity to food storage. Washing machines needed water access, drainage, and space for loading and unloading. Electric ranges imposed new safety and clearance requirements. These machines worked well but only if the environment they were placed in was able to support them. As such, homes changed. Freestanding furniture was replaced with built-in cabinetry. Countertops were standardized in height. Storage migrated closer to points of use. Kitchens shrank or reorganized to reduce unnecessary movement. And utility spaces emerged as purposeful places rather than afterthoughts crammed into the home.

This transformation was not aesthetic nor simple but manufacturers actively promoted spatial reconfiguration as part of appliance adoption. The Hoosier Manufacturing Company’s Kitchen Plan Book explicitly framed the kitchen as a system, offering modular layouts designed to “simplify the work which a woman must do in her kitchen.” In Europe, the Frankfurt Kitchen made this logic even more explicit: compact, labeled, and organized around a fixed set of tools and tasks.

From left: Radford’s Details of Building Construction, 1911; Frankfurt Kitchen, 1926-27; Architectural Graphic Standards, 1941; Architectural Graphic Standards, 1951

What matters here is not nostalgia for fitted kitchens, but the logic that underpinned them. Domestic space was redesigned because machines worked better when the environment cooperated. No one expected appliances to adapt to disorder indefinitely.

The space was asked to meet the machine halfway.

Diffusion: When Domestic and Industrial Spaces Learn from Each Other

Historically, the flow of efficiency knowledge moved from industry into the home. Taylorism, discussed above, informed household engineering; industrial motion studies shaped kitchen layouts. But this relationship has never flowed in only one direction. Domestic and industrial spaces have long taken inspiration from one another, borrowing techniques, layouts, and organizational strategies to achieve maximum efficiency.

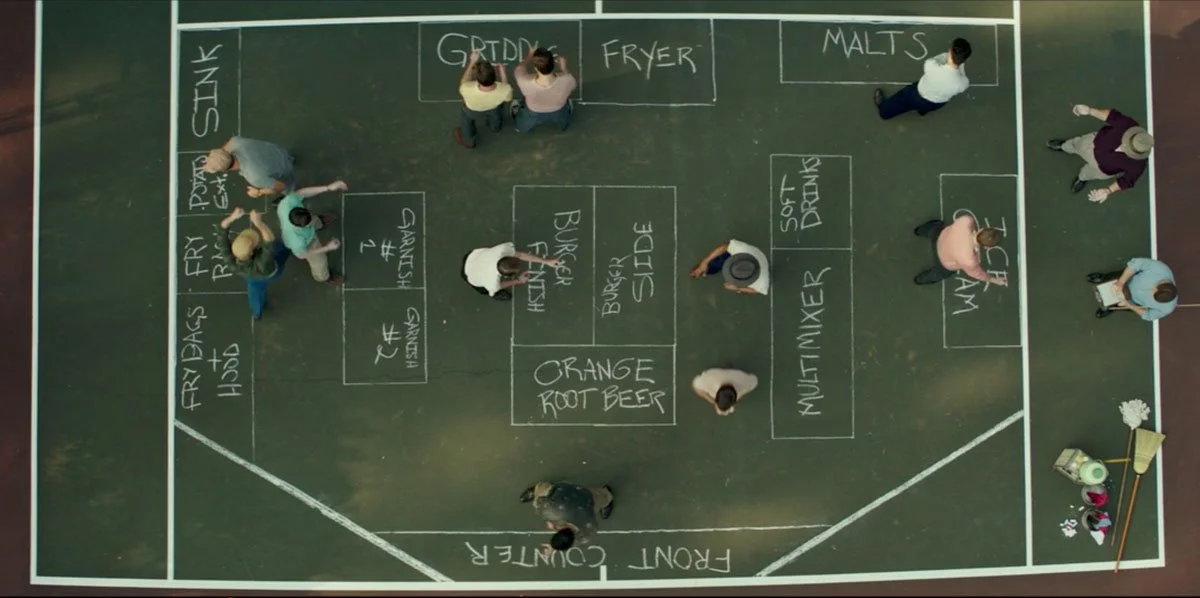

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, this feedback loop became especially visible in highly optimized service environments. Commercial kitchens, logistics centers, and fast-food operations demonstrate how spatial design, rather than intelligence alone, enables consistent performance at scale. Systems such as McDonald’s kitchens rely on extreme task decomposition, legible storage, constrained movement paths, and standardized interfaces. Error reduction comes not from individual expertise, but from environments that make deviation difficult. The lesson is not that homes should resemble fast-food kitchens. It is that efficiency emerges from the relationship between the laboring agent and its environment. When tasks are predictable and space is designed accordingly, both humans and machines perform better. When environments are more dynamic, even highly capable individuals will struggle with their tasks.

This insight matters because it reframes the current robotics debate. Rather than asking whether machines are intelligent enough to cope with domestic variability, we might ask why domestic environments are still so variable in the first place and whether all of that variability is actually necessary or worth the tradeoff we are making in eschewing robotic automation in order to maintain it rather than standardize.

Still from the Film, The Founder. McDonald’s layout.

When Kitchens Started Feeling Social and Stopped Working

By the latter half of the twentieth century, kitchens began to drift away from their role as engineered workspaces. Postwar prosperity, suburban expansion, and new cultural values reshaped domestic priorities. Kitchens grew larger and more open. Walls disappeared and the kitchen became increasingly central to life in the home not just functionally, but symbolically.

This shift brought undeniable benefits. Kitchens became more like social spaces, places for gathering and visibility. But this social transformation came at a cost. As service boundaries faded, storage capacity often decreased. Workflow became less important than openness. Surfaces multiplied and we began to spend more time in the kitchen but task zones blurred and with them the importance of efficiency was demoted. The kitchen was now expected to function as a workspace, dining room, office, classroom, and meeting point. This is an issue, however, because domestic labor did not disappear. It just became less visible, dispersed across a room optimized for presence over process.

Still from 1990s sitcom Friends showing a popular social setting of Monica’s Kitchen

This matters because it tracks the process through which modern homes became so poorly aligned with automation. The very features that make kitchens feel open and flexible like ambiguous areas, mixed functions, visual density, are precisely those that make structured task execution difficult for robotics and push robotic adoption and therefore the alleviation of domestic labor further and further out of reach.

Where the Robotics Field is Now and Why We Need to Change the Home First

Against this historical progression, it becomes easier to see why domestic robotics has struggled to take hold in the modern household. We are nowhere near creating and scaling generalist humanoid robotics capable of navigating cluttered, ambiguously designed homes with human-level contextual understanding and adaptability. That reality is often and easily acknowledged, but its next logical steps are rarely articulated, let alone acted upon.

As we have established, current robotic systems excel in environments that are structured, predictable, and machine- legible. They perform well when objects have consistent locations, when tasks follow repeatable sequences, and when movement paths are constrained. These are not marginal capabilities, they are the foundation of modern industrial robotics and account for the success of applied industrial robotics today.

Domestic environments, as currently designed, undermine and completely cut off the potential for these strengths. The inability for meaningful implementation of domestic robotics isn’t a failure of engineering alone. It is a failure of alignment between capability and environment. The problem is not that robotics is “not ready” for the home. It is that the home is “not ready” for the robot.

Combining Utility without Losing the Charm of the Home

Advocating for the industrialization of domestic space does not mean industrializing domestic life. My argument is and always has been historically grounded. Domestic industrialization applies to service zones: kitchens, laundry rooms, pantries, cleaning and staging areas, and delivery interfaces. These spaces are where repetitive, labor-intensive tasks are performed. They benefit from clarity, structure, and constraint and can be reconfigured and optimized while living spaces, by contrast, can remain human-centered, dynamic, and personalized. This division is not new but has been lost after being rooted in our culture for centuries. What has changed is not the need for this division, but our willingness to conform to it.

Reintroducing a combined utility room allows robotic systems to operate in a space where it can be most effective, without forcing automation on every aspect of domestic life and without necessitating the immediate achievements of the toughest hurdles in domestic robotics like variability and contextual understanding. To benefit from automation now we need to bring back the idea that some parts of the home are simply designed for work.

Designing the Bridge, Rather Than Waiting for the Leap

Every major shift in domestic innovation has followed the exact same pattern. New tools emerge with both capabilities and constraints. Then, our homes are redesigned to accommodate those realities. Over time, the tools invariably improve, environments adapt again, and the cycle continues.

Domestic robotics is no exception. Waiting for generalist humanoid systems before rethinking domestic space is an obvious historical mistake. The alleviation of labor has always come from aligning tools with their necessary optimal environments, not from waiting for tools to become perfectly aligned with what we have already.

Reconfiguring domestic service spaces today allows us to take advantage of robotics as it exists now, primarily in industrial environments, while laying the groundwork for more general systems in the future. This isn’t a detour and it’s not the end of the road but it is a lesson from history as the bridge we can stand on between where we are and where we want to go.

Works Consulted

Primary Sources

Frederick, Christine. Household Engineering: Scientific Management in the Home. Chicago: American School of Home Economics, 1919.https://archive.org/details/householdenginee00fredrich.

Gilbreth, Lillian Moller. The Homemaker and Her Job. New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, 1927.

Gilbreth, Frank B., and Lillian Moller Gilbreth. Applied Motion Study: A Collection of Papers on the Efficient Method to Industrial Preparedness. New York: Sturgis & Walton, 1917.

Hoosier Manufacturing Company. The Kitchen Plan Book. New Castle, IN: Hoosier Manufacturing Co., 1920.https://archive.org/search.php?query=Hoosier+Kitchen+Plan+Book.

United States Department of Agriculture. A Step-Saving Kitchen. Washington, DC: USDA, 1949.https://www.archives.gov/research/motion-pictures/highlights/a-step-saving-kitchen.

United States Department of Agriculture. Step-Saving U-Shaped Kitchen Plans. Washington, DC: USDA, 1948.https://archive.org/download/stepsavingukitch646unit_0/stepsavingukitch646unit_0.pdf.

Architectural & Design History

Schütte-Lihotzky, Margarete. The Frankfurt Kitchen. 1926.Museum of Modern Art Collection.https://www.moma.org/collection/works/87722.

Barr, Alexis. Commentary on early twentieth-century kitchen design. New York School of Interior Design. Quoted in The New York Times.

Phillips, Mark. Photograph of the Frankfurt Kitchen. Alamy Images.

Wright, Frank Lloyd. Willey House Kitchen Design, 1934.Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.https://franklloydwright.org.

Government, Education & Home Economics Collections

Cornell University Library. Home Economics Historical Collection.https://exhibits.library.cornell.edu/homeEc.

National Agricultural Library (USDA). Step-Saving Kitchens Collection.https://www.nal.usda.gov/collections/stories/step-saving-kitchens.

Library of Congress. Historic American Kitchens Photograph Collection.https://www.loc.gov/photos/?q=early+american+kitchen.

Smithsonian National Museum of American History. “Saving Time: Domestic Efficiency and the Modern Kitchen.”https://americanhistory.si.edu/ontime/saving/kitchen.html.

Smithsonian National Museum of American History. “Scientific Management and Efficiency.”https://americanhistory.si.edu/ontime/saving/.

Secondary Historical & Cultural Analysis

Wharton, Rachel. “Why Your Kitchen Looks Like That.” The New York Times, November 21, 2025.https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/11/21/realestate/kitchen-design-trends-history.html.

Viola, Dawn. Quoted commentary on historic kitchen placement and design. The New York Times.

Perera, Kishani. Quoted commentary on contemporary kitchen design. The New York Times.

Hull, Brent. Quoted commentary on millwork and kitchen history. The New York Times.

Barr, Alexis. Quoted commentary on Frankfurt Kitchen and early domestic standardization. The New York Times.

Design History & Popular Scholarship

Balchin, Anna. “When Kitchens Worked: The Rise and Fall of Functional Kitchens.” The Food Historian, 2020.https://www.thefoodhistorian.com/blog/when-kitchens-worked-the-rise-and-fall-of-functional-kitchens.

“Revisiting Kitchen Designs of the Early 20th Century.” Architect Magazine.https://www.architectmagazine.com/practice/revisiting-kitchen-designs-of-the-early-20th-century_o.

“Brief History of the Kitchen: From 1900 to 1920.” Apartment Therapy.https://www.apartmenttherapy.com/brief-history-of-the-kitchen-from-1900-to-1920-247461.

“A Brief History of Kitchen Design, Part 1: Pre-Standardization.” Core77.https://www.core77.com/posts/19771/a-brief-history-of-kitchen-design-part-1-pre-standardization-19771.

Industrial Design & Systems Thinking

Bennett, Khoi Vinh. “Design Lessons from McDonald’s.” Subtraction, January 23, 2018.https://www.subtraction.com/2018/01/23/design-lessons-from-mcdonalds/.

Robotics & Structured Environments (Conceptual Context)

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL). “Robotics Research.”https://www.csail.mit.edu/research/robotics.

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). “Robotics and Automation Learning Resources.”https://robots.ieee.org/learn/.

Reference Works

Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Scientific Management.”https://www.britannica.com/topic/scientific-management.

Wikipedia contributors. “Frankfurt Kitchen.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankfurt_kitchen.

Wikipedia contributors. “Kitchen Work Triangle.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kitchen_work_triangle.

Wikipedia contributors. “Lillian Moller Gilbreth.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lillian_Moller_Gilbreth.

This article was proudly written by Emily Genatowski with creative structural input and support synthesizing research from Chat GPT Model 5.2.